New Orleans Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs – Let the good times roll

Social Aid & Pleasure Clubs

Parades have been a part of New Orleans since the early days of the city. French troops would drill on the Place d’Armes, the city’s parade ground. The soldiers and band were considered the first line and other unofficial people joining in were called the second line of the parade.

The tradition of military parades slowly shifted into parades to send-off a deceased person. Families would hire a brass band to march from the church to the cemetery, and back to the family home. Limited resources forced people to pool money. They formed “social aid” societies to able to bury their dead with dignity. When “Jim Crow” laws came into being in the late 19th Century, only white musicians were allowed to play at social events or clubs, leaving the streets to black musicians. Their way of celebrating life got the community’s feet moving, quickly growing in popularity. The social aid societies evolved into pleasure clubs as well.

Brass parade

On Sundays, the only day off for workers in the former French colony, people would march behind brass bands winding their way through the streets in an energetic parade. Leaving the streets to black musicians also created a new music style: jazz. The up-tempo songs the bands played, improvising along the way combined with a pulsing rhythm were a call to the community at large to join in, to sing, dance and pass a good time.

These parades serve as social appropriations of the public space emphasising a strong cultural black identity. Yet, this form of collective dance also embodies a source of pride, not solely for the club members in their finest – the suit changes in cut, design and colour every season – but for other participants as well.

This is Nola, our city

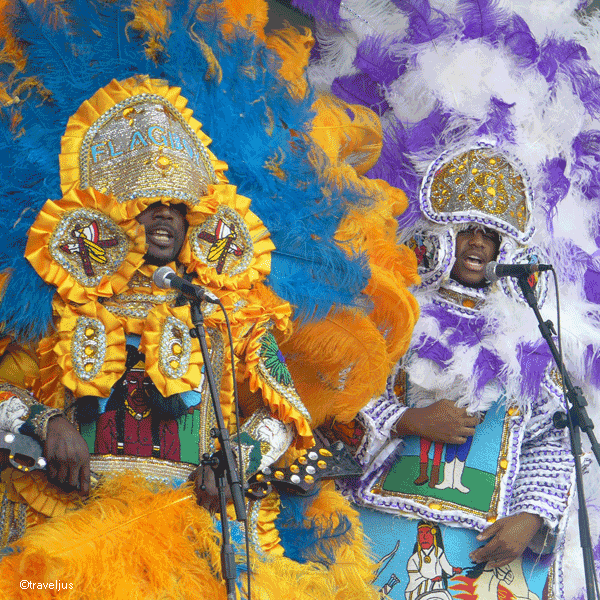

One afternoon we went to JazzFest to run into chanting and dancing members of a brass band waving ostrich-plume fans, wearing suits and hats in vibrant colours. Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs provide, besides entertainment, parades etc. a financial safety net for health care and burial services as well. The parades became particularly important after Katrina.When they form a route behind the mainline, also known as second lines, everybody has the opportunity to be part of the parade. This collective perseverance and triumph over adversity gave Nola residents a renewed feeling of community: “We are New Orleans, and this is our city”. The parades create a safe space for people from all walks of life to dance together, rub shoulders with the band, or walk at a leisurely pace, meanwhile eating, drinking and catching up with old and new friends.

A brief history of the city of New Orleans

New Orleans was passed by lots of times in the 16th and 17th centuries, yet it was not until 1718 when Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville founded La Nouvelle Orléans and built a central hub around Place d’Armes. After a hurricane destroyed most of the city in 1722 the streets were rebuilt in a grid pattern, the later French Quarter.

The French ruled over the city until 1763, after which Louis XV gave the territory to his cousin Charles III of Spain. The Spanish influence is still visible in some of the street signs in the French quarter. When King Charles IV of Spain signed the royal decree to transfer the territory back to France in 1800 it was only temporary. To secure American commerce access to the Mississippi and the port of New Orleans, Thomas Jefferson purchased the colony from Napoleon, who was in desperate need of money. In 1803 the U.S. became the proud owner of approximately 827,000 square miles of Louisiana territory, including New Orleans, for the stately sum of fifteen million dollars.